Going beyond the buzzwords, MLS News speaks with legal experts about ‘design thinking’ – how it works, what it means for lawyers, and the impact it can have for clients and the public.

By Catriona May

Going beyond the buzzwords, MLS News speaks with legal experts about ‘design thinking’ – how it works, what it means for lawyers, and the impact it can have for clients and the public.

- The Hon. Robert Stanley Osborn (LLB(Hons)'72, LLM'76)

- Judge Gerard Mullaly (LLB'86)

Google ‘legal design’ and you will receive hundreds of pages of results – consultancies offering legal design expertise, articles titled ‘Why every organisation needs legal design’, and even information about the annual Legal Design Summit in Finland. But the term itself is relatively new.

Stanford academic Dr Margaret Hagan first coined the term in 2013 and, since then, it has become an increasingly talked about trend in law.

Hagan, who is also the Neota Logic Visiting Fellow at Melbourne Law School, was clearly onto something when she launched the Legal Design Lab, which has one foot in Stanford Law School and the other in the d.school, the university’s well-regarded design faculty.

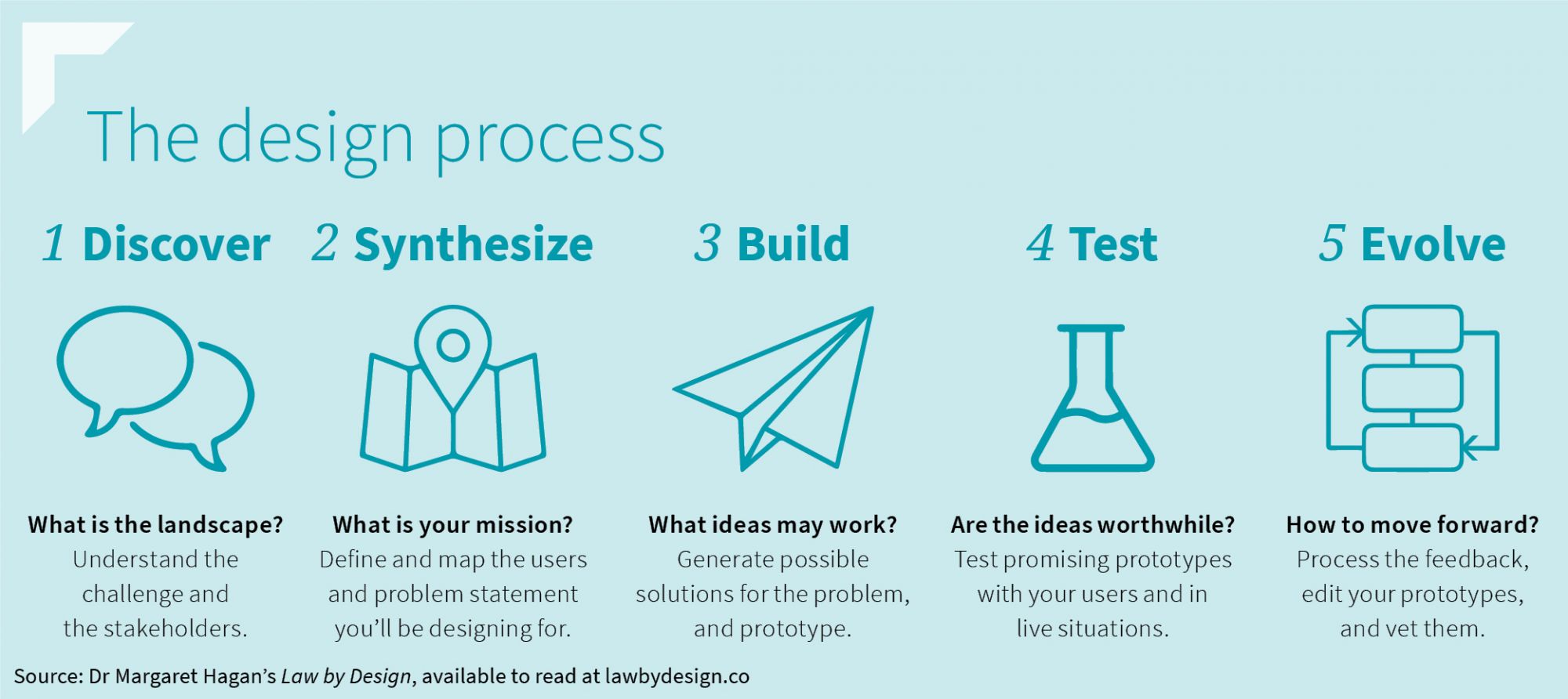

Fundamentally, legal design is about improving the experience of law for everyone within the system by placing humans at the centre of decision-making. In her book Law by Design, Hagan writes that design thinking is a methodology that offers a “path to follow” to tackle the “many frustrations, confusions and frictions in law”. It involves a stepped approach of research, product prototyping and testing prior to implementation.

We need to talk to users, check our assumptions, and spend a minute outside of our offices and away from our boardrooms.

As Hagan writes in her book, “Legal design is a way of assessing and creating legal services, with a focus on how usable, useful, and engaging these services are.”

Improving access to justice

While legal design holds promise across the profession, its potential to improve access to justice is what sparks Hagan’s interest the most.

“In California the number of self-represented litigants in the civil system is skyrocketing,” she says, with “the high cost of lawyers, mistrust in the legal system, and a feeling that with Google we can all be lawyers” all contributing factors. Australians face similar barriers to justice, with only half of the people who have moderate or severe legal problems able to get the legal help they need.

Hagan says that when people find themselves with five days to respond to an eviction notice or 30 days to respond when a credit card company sues them, the legal system can be so difficult to penetrate without a lawyer that it often compounds their problems. In her experience, while equal access to justice may be a core principle of the system, it is not happening in practice.

“These people won’t get lawyers any time soon. We need some sort of capability to get procedural justice or substantive justice for them, or we need to redesign the system so it is less burdensome for people to access.”

Her team applies design thinking to address some of these very real issues, coming up with solutions like fliers and posters that explain how to navigate complicated court processes, or a messaging tool that courts or legal services can use to send automated messages to their clients.

Hagan’s work already resonates in Australia. Kate Fazio (LLB ’09) heads up innovation and engagement at Justice Connect, an organisation that helps individuals and not-for-profits access legal support. When she came across Hagan’s work on legal design in 2016, she was excited to discover that the kind of work she was doing was part of a wider global movement. And Hagan’s terminology gave her the language to discuss it.

Fazio and her colleagues had started an ambitious business transformation project to improve how they engage with stakeholders. Embracing the legal design process, their model involves thorough research with end users, prototyping, testing and evaluation. When a product meets minimum viability, it is released and continues to be reviewed and improved iteratively.

It means the products they produce, like their new online intake tool or their portal to connect pro-bono lawyers with clients, are “highly validated, and put the voices and needs of people at the centre of the work,” says Fazio.

With sophisticated technology improving access to many other professions and services, she says it is time to start tackling the barriers many people face when trying to access justice. “The design lens has an important role to play in how we take those barriers down.”

For Hagan, legal design brings an alternative frame to how lawyers traditionally think.

“The method and mindset of design thinking force us into a place of humility and service,” she says. “One of the major professional flaws of lawyers is a ‘there’s no problem we can’t solve’ attitude. But most of the problems we encounter in access to justice are complicated, systemic and hard to solve.”

Changing corporate culture

Corporate firms are starting to show interest in design thinking too, which Hagan welcomes as a potential shift in culture.

“They’re becoming more entrepreneurial, showing more empathy and nurturing innovation,” she says. “It can help retain staff, which, of course, will ultimately make them

more competitive.”

Blake Connell (JD ’17), a solicitor at Herbert Smith Freehills, was recently named a Rising Star at the Law Institute of Victoria’s Victorian Legal Awards. He agrees with Hagan, saying that while legal design might not be for every lawyer,

for those who are interested, it can expand their role beyond a sometimes narrow set of outputs.

“Law has always been a noble profession and for a long time it’s been immune to the forces that have compelled other sectors to compete,” he says. “But that’s being ripped away now. People are starting to say, ‘if my lawyer isn’t effective for me, I’ll go to someone else’.”

Connell says design thinking can help lawyers better address clients’ needs because it encourages them to adopt an empathetic mindset, rather than jumping straight to a solution. His own interest lies in using visuals to make text-heavy documents like contracts and policies, as well as complicated legal processes, accessible to the “widest range of people possible”.

“Design thinking could lead to a new generation of lawyers producing innovative solutions that we don’t necessarily associate with lawyers at the moment, and that could change

the whole face of the profession.

Being at a firm that supports this kind of work means I can see the benefits of design thinking up close; it injects energy and creativity, which benefits everyone.

Building justice into the courts

While legal design is encouraging a new way of thinking about how the law is practised, the new Shepparton Law Courts, which were opened earlier this year, give an indication that the principles of human-centred design are already making a mark on the bricks and mortar of the law.

“Being in a post-colonial country, historically what happened was that buildings were designed by a government architect in an office a long way away. It didn’t matter much if you were in Ireland or in Shepparton,” says Justice Robert Osborn (LLB(Hons) ’72, LLM ’76), who represented the Supreme Court of Victoria on the steering committee that guided the new building’s design.

“We’ve come a long way from that way of thinking.”

It was important the new building “felt like the Shepparton court, not some centralised institution”, says Osborn. Part of that involved working with local Indigenous artists to feature their work in the finished court.

Having a local court is significant – one that jurors feel is their court, that people who have suffered through crime feel is their court, and that the people on trial and their families all feel is their court too.

The layout of the multi-jurisdictional courts was carefully considered, so that the finished building became a place “where we did justice differently, rather than a bigger box where we did what we had always done.

The architects considered the design from multiple user perspectives, consulting with victim support workers, Legal Aid, Victoria Police, court staff, the judiciary and Elders from the local Indigenous community. They worked closely with stakeholders, testing their ideas. This included setting up a mock courtroom in a warehouse, where judges and other stakeholders could provide feedback on the layout – a step that helped improve sightlines.

Judge Gerard Mullaly (LLB ’86) represented the County Court on the building’s steering committee. “People who are in a court case are stressed enough – we wanted the entire building to be as straightforward for them as we could,” he explains.

“The Royal Commission into Family Violence really brought to the fore how the experience of a courthouse can be frightening and intimidating, because it brings people into close proximity with the perpetrator. We had to design a place where we could safely separate parties without being too obvious or restrictive.”

Osborn says experimentation is at the heart of legal design, and it is an important practice to embrace. He points to the establishment of the Koori Court in 2002 as an example which has gone on to reduce recidivism, particularly among young Indigenous people who find themselves in the justice system.

“When we know something isn’t working, we need to experiment to find new approaches,” he says. “If we don’t try when we have serious problems, there can be a sense of despair in the community and among practitioners.”

Hagan is optimistic about the potential for legal design practices to reshape the legal system, both here in Victoria and in her native California.

There’s a common movement in both jurisdictions to serve people better in the legal system,” she says. “And it’s shared by regulators, bar associations and court associations. In Victoria in particular, I have seen a willingness to take different regulatory approaches, to ask questions and seek answers. It’s exciting to see.

In some cases, legal design will change the way clients and lawyers interact; in other cases, it might help simplify complex legal frameworks. In Shepparton, it has already changed the physical embodiment of justice and the law. As Mullaly puts it: “It’s become very clear that the design of the court and the way you move around it are fundamental to people’s sense that the place is somewhere they can access justice. The development of human-centred design in courts is as important as many other reforms in the area of access to justice.”

Banner image: The Shepparton Law Courts foyer

Credit: Scott Burrows

This article originally appeared in MLS News, Issue 22, November 2019