March 2021

In this blog, Director of Road to Refuge, Jeanine Hourani, reflects on efforts to change the narratives around statelessness by amplifying the voices of people with lived experience. She draws on her engagement as a refugee and statelessness advocate, public speaker, writer, and educator, to underline the importance of building the storytelling capacity of stateless individuals – a key focus of her organisation’s work.

Statelessness isn’t a passive concept; it is inflicted on individuals by the (in)action of States. Statelessness isn’t something that I am (or was), it is something that was inflicted upon me. Those of us who are privileged with statehood often forget how contingent our basic human rights are on our status as citizens.

Born as a stateless Palestinian refugee, I arrived to Australia on stolen land of the Indigenous Wurundjeri people on February 23rd, 1997. All the rights and privileges I had access to growing up (from my right to healthcare and education, to freedom of movement) were only accessible to me because of my status as an Australian citizen. Citizenship was ultimately granted to me by Australian laws and government departments, which had been built upon the colonisation and dispossession of First Nations people. Settler colonisation of my own homeland led me here, where I became and continue to be a benefactor of the settler colonisation of this land that we now call ‘Australia’.

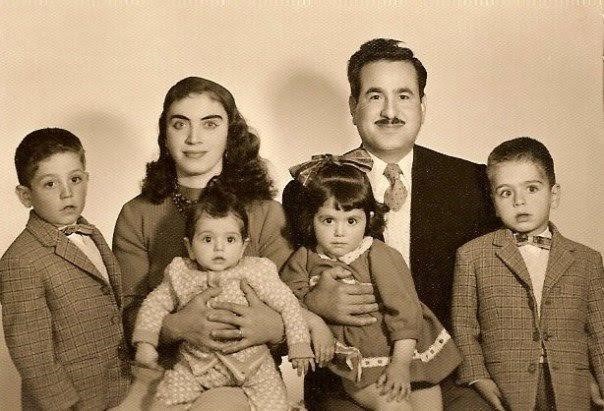

My grandparents were expelled from the Palestinian homeland in 1948; collateral damage in the creation of the State of Israel. We Palestinians refer to this as ‘The Nakba’. My mother is Lebanese; gender-discriminatory laws make it so that Lebanese citizenship can only pass through paternal lines. I was born stateless because my Palestinian father had no citizenship to give me and my mother was prohibited from giving me hers. I was born in Bahrain, a country that has no legal protection for children who are born stateless.

Statelessness has been passed on in my family for three generations. When you come from generations of statelessness, you are aware of both the lived reality of what it means to exist without citizenship, and the total power that States hold in the global citizenship regime. States give and take away your rights, they decide who is ‘in’ and who is ‘out’, and they can ultimately grant or revoke citizenship. Statelessness harms individuals who are impacted by the phenomenon, and States hold the power in global citizenship infrastructure to create and maintain this harm. Why, then, do we continue to talk about statelessness as a deficit of the ‘vulnerable’ stateless individual, and not a problem created by the States that create these vulnerabilities?

We need a narrative on statelessness that exposes it not as an individual deficit, but as a result of broken systems and structures that put individuals in harm’s way.

Currently, the way statelessness is discussed (whether it’s by the media, academics, UN agencies, or non-profits) often erases stateless individuals from the narrative. If and when stateless people are included in the narrative, it tends to be done in a way that strips them of their agency and autonomy. The language used to talk about statelessness often centres the tension between UN agencies and States. This erases those directly impacted by statelessness from the conversation. Stateless people become mere by-standers, rather than being considered as the individuals who are directly impacted by the issue and should thus be the centre of the narrative.

If and when stateless people are included in the discourse (never mind actually given the platforms to speak for themselves) they are talked about using deficit-based language. For example, words like ‘vulnerable’, ‘invisible’, and ‘voiceless’ focus on what an individual does not have; it could even be argued that the word ‘stateless’ is itself deficit-based. There is no doubt that highlighting what an individual does not have access to (e.g. citizenship) is important in highlighting injustices. However, this can also be harmful. While the term stateless (although perhaps deficit-based) is an accurate statement, there is no such thing as the ‘voiceless’ or ‘invisible’, only the silenced and forgotten. Deficit-based language deems stateless individuals responsible for their situation as opposed to the systems, structures, and institutions that have failed them.

If we want to address the root problem of statelessness, we need to critically reflect on who has power to create and maintain statelessness. We also need to actively work to transfer that power back to stateless people. Transferring power begins with changing the narrative. By changing the narrative on statelessness, we can shed light on the injustices caused by the phenomenon, as well as who is responsible for the phenomenon at large. Changing the narrative can also change our perception of who holds power by accurately depicting stateless people as autonomous individuals with a right to determine their own narrative and, by extension, their own lives. Changing the narrative includes both changing the language that is used to talk about statelessness, and platforming the voices and experiences of those most directly impacted. As stateless people, so many of our rights get taken from us but our stories and our perspectives have, and will always, belong to us. It is only when they are platformed and amplified in a genuine way that we will truly be able to eradicate statelessness.

More from the Critical Statelessness Studies Blog Series

The CSS Blog serves as a space for short reflective pieces by individuals working on statelessness from a critical perspective. Click here to learn more about the CSS project or here to read about how to contribute to the blog.