William Ah Ket – Australia’s first lawyer of Chinese descent

Associate Professor Andrew Godwin is researching the life and times of MLS alum William Ah Ket and is working with the descendants of the Ah Ket family for this purpose. Andrew and MLS would be delighted if any readers have information about William that they would like to share. Contact Andrew at a.godwin@unimelb.edu.au.

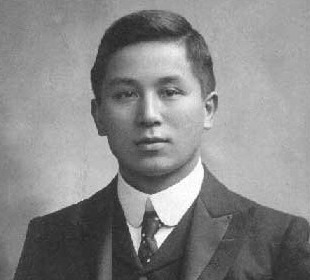

William Ah Ket as a young man

Source: by kind permission of the Ah Ket family

‘William Ah Ket (1876-1936), barrister, was born on 20 June 1876 at Wangaratta, Victoria, only son and fifth child of Ah Ket, storekeeper and grower and buyer of tobacco, and his wife Hing Ung, who were married in Melbourne in 1864. His father had arrived in Victoria in 1855 and after some years on the goldfields established one of the earliest tobacco-farms on the King River. He became the leading Chinese in the district and a respected member of the Wangaratta community.’

So begins the biography of William Ah Ket [麦锡祥] in the Australian Dictionary of Biography. An alum of the University of Melbourne, William studied jurisprudence in 1897 before joining law firm Maddock & Jamieson (now Maddocks) and commencing the articled clerk’s course at the University in 1898.[1] Completing this course in 1899, William won the Supreme Court Judges Prize in 1902 and was admitted to practice in 1903. He went to the bar the following year and is widely understood to have become the first Australian lawyer of Chinese descent to practise as a barrister at the independent bar in Victoria.[2] William stayed involved with the University and was elected the President of the Law Students’ Society on 19 April 1907.

From this summary of his early achievements, it is clear that William was a gifted student and lawyer, who succeeded in a time rife with racial discrimination. So how is it that such a pioneering lawyer of Chinese descent is not more widely known?

Wangaratta Primary School, which William Ah Ket attended as a child.

Source: Andrew Godwin

Fast forward to 9 October 2019 when an audience of some 50 persons are gathered in the Great Hall of the High Court of Australia to attend the third award ceremony for the William Ah Ket Scholarship – a scholarship established by the Asian Australian Lawyers Association and supported by Maddocks. The keynote address is delivered by Chief Justice of The High Court of Australia, the Honourable Susan Kiefel AC, who makes the following comments:

‘By all accounts, Mr Ah Ket was a remarkable man. Despite his high profile and achievements, it would seem that others were advanced while he was not.[3] He was neither appointed Silk nor a judge. Sir Robert Menzies wrote that he and Mr Ah Ket "were great friends". He said that "William Ah Ket did not ever sit on the Bench, though he would have been a very competent judge. … He was a sound lawyer and a good advocate". He added, "A certain prejudice among clients against having a Chinese barrister to an extent limited his practice, though instructing solicitors thought very well of him".[4]

Despite, or perhaps because of, having himself been discriminated against, Mr Ah Ket devoted his life to fighting against unfair discrimination. He advocated and promoted “peaceful coexistence”.[5]

His answer to the difficulties he faced appears to have been to succeed in what he did; to be a real part of the legal profession; to help others and to act at all times righteously, with courage and with kindness. It is fitting and proper that this scholarship is named for him.’[6]

The recipient of the Scholarship, Tienyi Long, notes that ‘[l]awyers, courts and legislators continue to grapple with the question of how equal justice can be achieved for diverse communities in a multifaceted and increasingly complex society … diversity intelligence is an essential skill to facilitate equal access to justice for diverse communities … it should be included as part of mandatory continuing professional development requirements under the Legal Profession Uniform Law.’[7]

After the formalities conclude, enthusiastic discussion ensues among the guests about William and his legacy and includes a combination of questions and observations: ‘How is it that William Ah Ket is not more widely known?’; ‘William was certainly ahead of his times’; ‘Isn’t it remarkable that William managed to achieve so much despite the discriminatory policies of the time’.

William was particularly active in the fight against racial discrimination. In addition to lobbying against discriminatory legislation, such as the Immigration Restriction Bill of 1901, William appeared in many cases that we would describe today as ‘public interest’ cases.

In a High Court case called Ingham v Hie Lee,[8] Ah Ket represented a Chinese laundry owner who was charged with an offence under the Factories and Shops Act 1905 in Victoria. The act expressly discriminated against the Chinese and prohibited after-hours work in a factory or work-room where furniture was made or where any Chinese person was at any time employed. The reason why the Chinese laundry owner had been charged was that a Chinese man had been found in the laundry between 9 and 10pm at night ironing a shirt, apparently in breach of the after-hours work prohibition. Ah Ket’s legal team successfully proved that the Chinese man was not an employee of the laundry but instead a boarder at the laundry who had simply been ironing his own shirt!

Ah Ket appeared in another High Court case called Potter v Minahan,[9] where he represented a man born in Australia of a Chinese father and a white Australian mother. At that time, people born in Australia were British citizens by right, regardless of their parents’ origins. His father had taken him to China when he was about five years old. After living in China for many years, he returned to Australia as an adult, but was treated as a prohibited immigrant because he failed a dictation test imposed by the immigration legislation at the time. The test required all immigrants from China to write in English or another European language a passage of approximately 50 words, dictated by a customs officer. Ah Ket’s legal team successfully proved that he was not a prohibited immigrant. In its decision, the High Court found that if the immigration legislation had intended to remove the rights of citizenship, it should have expressed its intention clearly. In a passage that is still recognised as current law in Australia, Justice O’Connor stated as follows:

‘It is … improbable that the legislature would overthrow fundamental principles, infringe rights, or depart from the general system of law, without expressing its intention with irresistible clearness …’[10]

Despite the bamboo ceiling that William must have encountered during his life and career, it appears that his mission was to remove barriers and, as his daughter Toylaan Ah Ket wrote, to implement ‘his personal philosophy of building bridges between the East and West.'[11]

William’s focus on reconciliation is reflected in the Second Morrison Lecture that he delivered in 1933, where he discussed whether there was a real difference between the culture of the East and that of the West, and drew parallels between Western culture and Confucianism. Noting that music had a peculiar charm for Confucius, he mused that had Confucius lived then, ‘it is quite likely that he would have found in the music of the bagpipes something particularly stirring and satisfying to the soul.’[12] William would have had an affinity with bagpipes as his wife, Gertrude Bullock, was of Scottish descent.

William Ah Ket in Selborne Chambers, Melbourne circa 1933.

Source: http://monumentaustralia.org.au/

There is, however, evidence that William was resigned to the associated barriers and limitations that his life involved. The biography of Joan Rosanove QC, an alumna of Melbourne Law School and the first Jewish woman in Australia to be admitted as a barrister, contains the following reference to a light-hearted discussion between William and Joan:

‘A Melbourne barrister, Mr Ah Ket, a friend of Mark’s [Joan’s father], said to her, ‘You and I have both chosen the wrong profession, Joan. We will never satisfy our ambitions. Neither of us will ever be made a judge, you because you are a woman. I because I am Chinese. We should have done Medicine.’[13]

There are many more interesting stories and facts that one could relate about William and his legacy. For example, in addition to a busy life at the bar, William Ah Ket spent time as a diplomat, serving as acting consul-general for China in 1913-1914 and in 1917. In addition, William Ah Ket possessed a deep knowledge of the Western classics and modern languages and was wont to include ‘quotes from Shakespeare, the Scottish poet Robert Burns or a Gilbert & Sullivan opera’ during his appearances in court.[14]

If you have any further information about William’s life that you would like to share, I would warmly welcome your contributions.

– Andrew Godwin

[1] Helen Penrose, To Build a Firm: The Maddocks Story (Maddocks, 2010), 11

[2] See William Lye OAM, ‘Introduction to William Ah Ket at the Victorian Bar and Scholarship’ (William Ah Ket Inaugural Scholarship Launch at Maddocks, 21 November 2017), available at https://static1.squarespace.com/static/54dd81c6e4b074b4a339bb2e/t/5a1409caf9619a97a1396f77/1511262667464/WILLIAM+AH+KET+launch.pdf.

[3] Citing Karin Derkley, “William Ah Ket Legacy Recognised” (2018) 92(3) Law Institute Journal 83 at 83, 84.

[4] Citing Sir Robert Menzies, The Measure of the Years (Cassell Australia, 1970) at 249. Sir Robert Menzies practised with William in Selborne Chambers.

[5] Citing Toylaan Ah Ket, “William Ah Ket—Building Bridges between Occident and Orient in Australia, 1900-1936” (Chinese Studies Association of Australia, Macquarie University, July 1995) at 9.

6] The Hon Susan Kiefel AC, Chief Justice of Australia, ‘William Ah Ket’s contribution to diversity in the legal profession’ (Asian Australian Lawyers Association, William Ah Ket Scholarship Presentation, Great Hall, High Court of Australia, Canberra, 9 October 2019, 5:30pm).

[7] William Ah Ket Scholarship 2019, Program (9 October 2019).

[8] (1912) 15 CLR 267.

[9] (1908) 7 CLR 277.

[10] (1908) 7 CLR 277 at 307.

[11] See Toylaan Ah Ket, ‘William Ah Ket - Building Bridges between Occident and Orient in Australia, 1900-1936’ (paper delivered at the Conference of the Chinese Studies Association in Australia held at Macquarie University on 5 July 1995), available at https://arrow.latrobe.edu.au/store/3/4/5/5/1/public/stories/wahket.htm.

[12] William Ah Ket, ‘Eastern Thought, with special reference to Confucius’ (Second Morrison Lecture, 3 May 1933), available at https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/bitstream/1885/145813/2/Morrison%20Oration%2002.pdf.

[13] Isabel Carter, Woman in a Wig: Joan Rosanove, QC (Lansdowne Press, 1970), 13.

[14] Karin Derkley, above n 6.